Historical Development of Parapsychology

Before the scientific era and the age of enlightenment, stories of unexplained events and unearthly encounters were told and have been passed down to the current day. From mediums in the Old Testament (Samuel 28:7-12, 1010BC) and haunted houses in ancient Greece (Pliny the younger, 61-115AD) to the modern day spoon bending skills of Uri Geller (1946) and the Extrasensory Perception (ESP) abilities of Bob Cassidy (1949). Wherever mankind has been, stories shrouded in spooks, spectres, magic and miracles have followed in their wake. Firstly as superstation and folklore, then as unholy and unnatural, and now as events that lie outside scientific explanation and/or hoaxes.

Although these types of phenomena have feared and fascinated generations (be it for personal curiosity or entertainment values), studies undertaken by the scientific community to theorise and examine these occurrences are unfortunately low in volume, compared with other academic disciplines such as physics or chemistry. From the works and methods of researchers: Anton Mesmer; (1734-1815), Frederic Myers; (1843-1901), J.B. Rhine; (1895-1980) and John Beloff; (1920-2006) the subject of these unusual events has been lifted from its occult practices and stage act beginnings to the study of psychical research and ultimately the scientific field of Parapsychology.

“Scientific incredulity has been so long in growing, and has so many and so strong roots, that we shall only kill it, if are able to kill it at all regards any of those questions, by burying it alive under a heap of facts.” Sidgwick, (1882)

Although these types of phenomena have feared and fascinated generations (be it for personal curiosity or entertainment values), studies undertaken by the scientific community to theorise and examine these occurrences are unfortunately low in volume, compared with other academic disciplines such as physics or chemistry. From the works and methods of researchers: Anton Mesmer; (1734-1815), Frederic Myers; (1843-1901), J.B. Rhine; (1895-1980) and John Beloff; (1920-2006) the subject of these unusual events has been lifted from its occult practices and stage act beginnings to the study of psychical research and ultimately the scientific field of Parapsychology.

“Scientific incredulity has been so long in growing, and has so many and so strong roots, that we shall only kill it, if are able to kill it at all regards any of those questions, by burying it alive under a heap of facts.” Sidgwick, (1882)

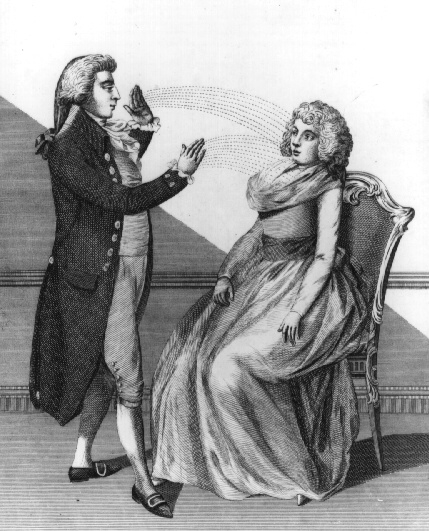

Franz Anton Mesmer (1733-1815)

|

While experimenting on the healing effect of magnets and their influences on physiological functions (e.g. blood flow rates), Mesmer believed he had identified a new type of energy that flowed throughout the universe, and that the distribution of this energy within the body had a direct result on an individual’s health. An unbalanced energy flow could manifest itself as a number of different neurological diseases/disorders. Treatment would involve addressing this imbalance by using the energy (termed ‘animal magnetism’) of a healthy magnetiser, and transferring this to the patient. Initially Mesmer utilised magnets in the healing process, but after a brief period he discovered that they were unnecessary and that by passing his own hands or lightly touching the patient the same effect could be obtained. (Beloff, 1993)

One of Mesmer’s first patients (in 1773) was a woman who suffered from convulsions brought on by a hysterical disorder. Mesmer found that by using his method he was able to control her convulsions and through this success, his treatment and name spread, bringing an increase in patients and making the technique highly fashionable. |

At first the fits/seizures associated with the disorders that Mesmer treated were a common occurrence, but after viewing the method conducted by one of his students (Marquis de Puysegur) where his patients would fall into a sleep-like state instead, this affect became more general and the convulsive aspect less common. This change in symptom response has been theorized to it being culturally transmitted, whereby individuals have a certain idea of what behaviour they are expected to show, changing from convulsions to a sleep-like state, Lynn & Kirsch. (2006).

|

Mesmer’s technique eventually became the foundation of hypnosis, but for parapsychology, his name is associated with a behaviour displayed by some of his patients while in this sleep-like state, termed ‘higher phenomena’. Patients would report being able to have the ability to gain access to information/events that were sensorial inaccessible to them (i.e. describing the actions of an individual in another room) and this led to studies being carried out, into using this state to evoke different types of experience e.g. telepathy / clairvoyance. With the outcry made by the medical community in France against mesmerism, (seeing it as a threat to their establishment) two commissions were set up to examine its claims.

The results were applauded when both came back negative (Beloff, 1993). It is this research carried out on mesmerism’s high phenomena which resulted in the first examination of parapsychological phenomena being investigated outside the framework of occultist and quasi-religious settings. The results also found that by controlling test conditions, the researcher could help establish authenticity of the phenomena (Irwin & Watt, 2007). From these outcomes, mesmerism can be considered a major factor in the origins of parapsychology. |

Spiritualism and The Society of Psychic Research (SPR)

|

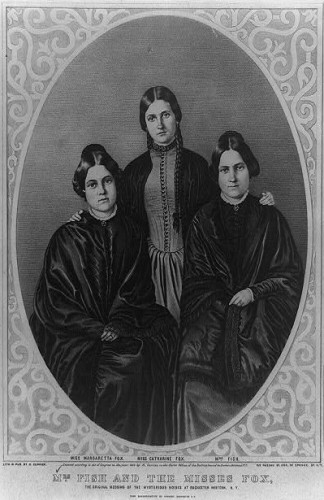

Spiritualism, which saw public interest increase in 1850 with the activities of three sisters and their reported ability to communicate with the deceased through séances. Thanks to the Fox sisters, the spiritualist movement rapidly gained momentum in both the US and Europe, so by the mid 1850’s a new highly fashionable phenomena had begun with self-acclaimed mediums of every social branch willing to help anyone get in contact with the departed. But now not only were they offering communication, but also more physical evidence of their abilities, (termed physical mediumship) e.g. the materialisation of spirit faces or forms within a darkly lit séance room. With this increase in popularity, the financial benefits involved in offering a more amazing and unbelievable séance also increased, which in turn increased the temptation of fraudsters. It is largely due to this influx of claims, that a meeting between Sir William Fletcher Barrett (1844-1925), a physicist, and Dawson Rogers (1823-1910), a spiritualist, took place in January 1882, leading to the formation of a small group. |

This group took it upon themselves to investigate these claims and a number of different debatable phenomenons, in a scientific manner, using the same standards and methods carried out by sciences of the day, (e.g. observation and experimentation) (Gauld, 1968). In February of 1882 the Society of Psychic Research (SPR) was established. The founding members also included a group of Cambridge honorary fellows: Henry Sidgwick (1838-1900), a philosopher, (made president of the SPR) Frederic Myers (1843-1901), a classical scholar and poet, and Edmund Gurney (1847-1888), a psychologist. A number of notable spiritualists also joined, including Reverend William Stainton Moses, (1839-1892) and Morell Theobald (1828-1908). In all, the society held an assorted group of believers, sceptics, scientists and spiritualists from different social backgrounds.

This mixture of personality could be viewed as a good representation of well-educated and knowledgeable men, who all had an interest in pursing either the validation of the phenomena or exposing it as fraudulent. They saw this as a service to both the scientific community and the paying general public, but in practise this combination of character and class clashed and separated over investigation methods (Cambridge fellows, based on upper class rational and detached enquiry, and the spiritualists based on working/middle class democratic and common-sense) and on research areas (telepathy, coined by Myers, to the spiritualist core issue of survival of bodily death) (Hamilton, 2009).

This mixture of personality could be viewed as a good representation of well-educated and knowledgeable men, who all had an interest in pursing either the validation of the phenomena or exposing it as fraudulent. They saw this as a service to both the scientific community and the paying general public, but in practise this combination of character and class clashed and separated over investigation methods (Cambridge fellows, based on upper class rational and detached enquiry, and the spiritualists based on working/middle class democratic and common-sense) and on research areas (telepathy, coined by Myers, to the spiritualist core issue of survival of bodily death) (Hamilton, 2009).

|

Not only internal problems plagued the SPR, but also external ones. Campaigns from mainstream scientists viewed members as crack-pots or pseudo scientists, smearing any papers/journals released. Some of the mediums that the SPR had endorsed were held under suspicion of fraud (e.g. Florence Cook, Creery Sisters) and later in 1888 the confessions of Maggie Fox and their fraudulent practices (Neher, 1980). Throughout these difficulties the SPR continued to grow, including members such as Lewis Carroll (1832-1898), and Arthur Conan Doyle (1859-1930).The American SPR was founded in 1885 with notable members such as William James (1842-1910) and Sigmund Freud (1856-1939).

With the establishment of the SPR, it can be viewed as the first and largest organisation to research these types of phenomena, using scientific techniques and methods, and releasing journals, books and reports on their findings. |

From this, the SPR has its place as one of the main influencing stages in developing Parapsychology as a scientific discipline.

Joseph Banks Rhine (1895-1980)

|

Rhine believed that psychical research should be taken out of the hands of the societies and placed into the laboratories of universities, changing it into an experimental science. With this in mind and a chance meeting with William McDougall, a British psychologist, in 1926, Rhine changed his academic focus, from botany to psychology, and in 1929 worked under McDougall at Duke University as an assistant professor (Irwin & Watt, 2007).

Rhine wanted to create an experiment that followed the same scientific methods of other disciplines (e.g. quantitative data and statistical analysis) and one that could be applied to a large group. He sought help from fellow Duke Psychologist Karl Zener (1903-1964), and re-examined a card-guessing experiment conducted by SPR member Ina Jephson (1924-1928), which claimed to show results of clairvoyance, Jephson (1928). |

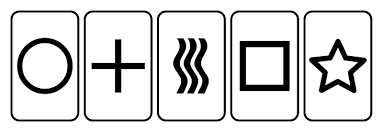

Rhine invited Zener to create a more simplistic card design, one that did not involve the problems displayed with using normal playing cards, (e.g. determining the target card -suit/ face value or both). From this invitation, the Zener cards were constructed, using five of five symbols; circle/star/plus/square/wavy lines. Using these cards Rhine set up various experimental techniques (BT – Basic Technique, DT – Down Through Technique) for testing clairvoyance and/or telepathy, depending on whether the researcher knew the symbol of the card (telepathy) or not.

|

In 1933 one study saw the gifted abilities of Hubert Pearce, a student, who on average scored between 8/9 hits per run (3/4 hits over the Mean Chance Expectations (MCE) of 5). Rhine requested his research assistant Gaither Pratt, to conduct a long-distance experiment with Pearce on the Duke University campus, ranging from 100 to 250 yards.

|

Both the tester (Pratt) and the participant (Pearce) were situated in different buildings. Using a Basic Technique, one card every minute would be removed from the top deck and place faced down without being examined, while the participant would mark his guess on a call-sheet. The results showed a significant difference over the MCE (1,850 trials, 558 hits over MCE 370) and provided experimental evidence for what Rhine coined in 1934 ESP (Extrasensory perception) (Beloff, 1993).

Although there has been much debate over Rhine’s report on the Peace/Pratt study (Irving Langmuir (Park, 2000, 42), Milbourne Christopher (1970) and Martin Gardner (1989), one critic, Mark Hansel, (1980) published a report stressing a large failure with the experiment: Peace was only observed in the final subseries of trails. When unobserved he could have, (without being heard or seen) sneaked to Pratt’s location and viewed the target cards being turned, thus recording the correct symbols.

To conclude this examination of parapsychology, one must consider the struggles this discipline has had to undertake to be accepted as a science. Just as many mainstream sciences were smeared by religious leaders for their theories before the scientific revolution, parapsychology has had to endure similar experiences during its early development (though not life-threatening, more academically ridiculed and ignored). With the fortunate popularity of both mesmerism and spiritualism in social attitudes of the time, this did allow parapsychology to be brought to the attention of the public domain, and more importantly to future researchers (Sidgwick and Myers research on thought-reading sparking an interest with Rhines work on ESP). One can see the stages taken to refine the methodology of this discipline: from passing curiosity/initial basic testing to greater observation/experimental subjection, then finally to statistical analysis and the principles of traditional scientific methods (Higher phenomena-thought-reading/telepathy-ESP). Held with a unique significance within the continuing debates of philosophy of the mind, due to the questions that parapsychology and its studies of psi phenomena, (ESP, PK, etc...) addresses. For example, has the capability and limitation of the mind been underestimated due to psi? How does psi affect the assumptions concerning the separation of mind/ body?

Although parapsychology is still a relatively new discipline, its development and recognition has increased rapidly since the 1930’s. The Parapsychology Association, established in 1957, promotes the advancement and integration of parapsychology in science, becoming an affiliated organisation of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) in 1969. The Koestler Parapsychology Unit at Edinburgh University, formed in 1984, researching various psi phenomena, followed closely by the research departments at Liverpool Hope University, Coventry University, Goldsmiths University and Northampton University.

With this growth in research, parapsychology advances.

Although there has been much debate over Rhine’s report on the Peace/Pratt study (Irving Langmuir (Park, 2000, 42), Milbourne Christopher (1970) and Martin Gardner (1989), one critic, Mark Hansel, (1980) published a report stressing a large failure with the experiment: Peace was only observed in the final subseries of trails. When unobserved he could have, (without being heard or seen) sneaked to Pratt’s location and viewed the target cards being turned, thus recording the correct symbols.

To conclude this examination of parapsychology, one must consider the struggles this discipline has had to undertake to be accepted as a science. Just as many mainstream sciences were smeared by religious leaders for their theories before the scientific revolution, parapsychology has had to endure similar experiences during its early development (though not life-threatening, more academically ridiculed and ignored). With the fortunate popularity of both mesmerism and spiritualism in social attitudes of the time, this did allow parapsychology to be brought to the attention of the public domain, and more importantly to future researchers (Sidgwick and Myers research on thought-reading sparking an interest with Rhines work on ESP). One can see the stages taken to refine the methodology of this discipline: from passing curiosity/initial basic testing to greater observation/experimental subjection, then finally to statistical analysis and the principles of traditional scientific methods (Higher phenomena-thought-reading/telepathy-ESP). Held with a unique significance within the continuing debates of philosophy of the mind, due to the questions that parapsychology and its studies of psi phenomena, (ESP, PK, etc...) addresses. For example, has the capability and limitation of the mind been underestimated due to psi? How does psi affect the assumptions concerning the separation of mind/ body?

Although parapsychology is still a relatively new discipline, its development and recognition has increased rapidly since the 1930’s. The Parapsychology Association, established in 1957, promotes the advancement and integration of parapsychology in science, becoming an affiliated organisation of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) in 1969. The Koestler Parapsychology Unit at Edinburgh University, formed in 1984, researching various psi phenomena, followed closely by the research departments at Liverpool Hope University, Coventry University, Goldsmiths University and Northampton University.

With this growth in research, parapsychology advances.

References

Beloff, J, 1993.Parapsychology: A concise history. 1st ed. New York: St. Martin's Press (New York).

Christopher, M., 1970. ESP, Seers & Psychics. 2nd ed. New York: Crowell.

Gardner, M.,1989. Science, Good, Bad, and Bogus. New York: Prometheus Books.

Gauld, A. 1968 The Founders of Psychical Research. London: Routledge & Regan Paul.

Hansel, C. E. 1980. ESP and Parapsychology: A Critical Re-evaluation. New York: Prometheus Books

Hamilton, T. 2009 Immortal Longings, FWH Myers and the Victorian Search for Life After Death. UK: Imprint Academic.

Irwin, H. J.& Watt, C., 2007. An introduction to parapsychology, 5th ed. North Carolina: McFarland & Company Inc.

Jephson, I., 1928, Evidence for Clairvoyance in Card-Guessing, Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 109, no.38

Lynn, S.J. & Kirsch, I, 2006. Essentials of clinical hypnosis: an evidence-based approach. New York: American Psychological Association.

Myers, F. W. H. 1894 - 1895. The Drift of Psychical Research. National Review 24, 190-209

Neher, A., 1980.The Psychology of Transcendence. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall

Park, R. L., 2000. Voodoo Science: The Road from Foolishness to Fraud. Oxford University Press.

Sidgwick, H. The Presidents Address, 1882. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research, 1, 7-12.

Beloff, J, 1993.Parapsychology: A concise history. 1st ed. New York: St. Martin's Press (New York).

Christopher, M., 1970. ESP, Seers & Psychics. 2nd ed. New York: Crowell.

Gardner, M.,1989. Science, Good, Bad, and Bogus. New York: Prometheus Books.

Gauld, A. 1968 The Founders of Psychical Research. London: Routledge & Regan Paul.

Hansel, C. E. 1980. ESP and Parapsychology: A Critical Re-evaluation. New York: Prometheus Books

Hamilton, T. 2009 Immortal Longings, FWH Myers and the Victorian Search for Life After Death. UK: Imprint Academic.

Irwin, H. J.& Watt, C., 2007. An introduction to parapsychology, 5th ed. North Carolina: McFarland & Company Inc.

Jephson, I., 1928, Evidence for Clairvoyance in Card-Guessing, Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 109, no.38

Lynn, S.J. & Kirsch, I, 2006. Essentials of clinical hypnosis: an evidence-based approach. New York: American Psychological Association.

Myers, F. W. H. 1894 - 1895. The Drift of Psychical Research. National Review 24, 190-209

Neher, A., 1980.The Psychology of Transcendence. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall

Park, R. L., 2000. Voodoo Science: The Road from Foolishness to Fraud. Oxford University Press.

Sidgwick, H. The Presidents Address, 1882. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research, 1, 7-12.